The digital leap in our forests is bringing considerable savings

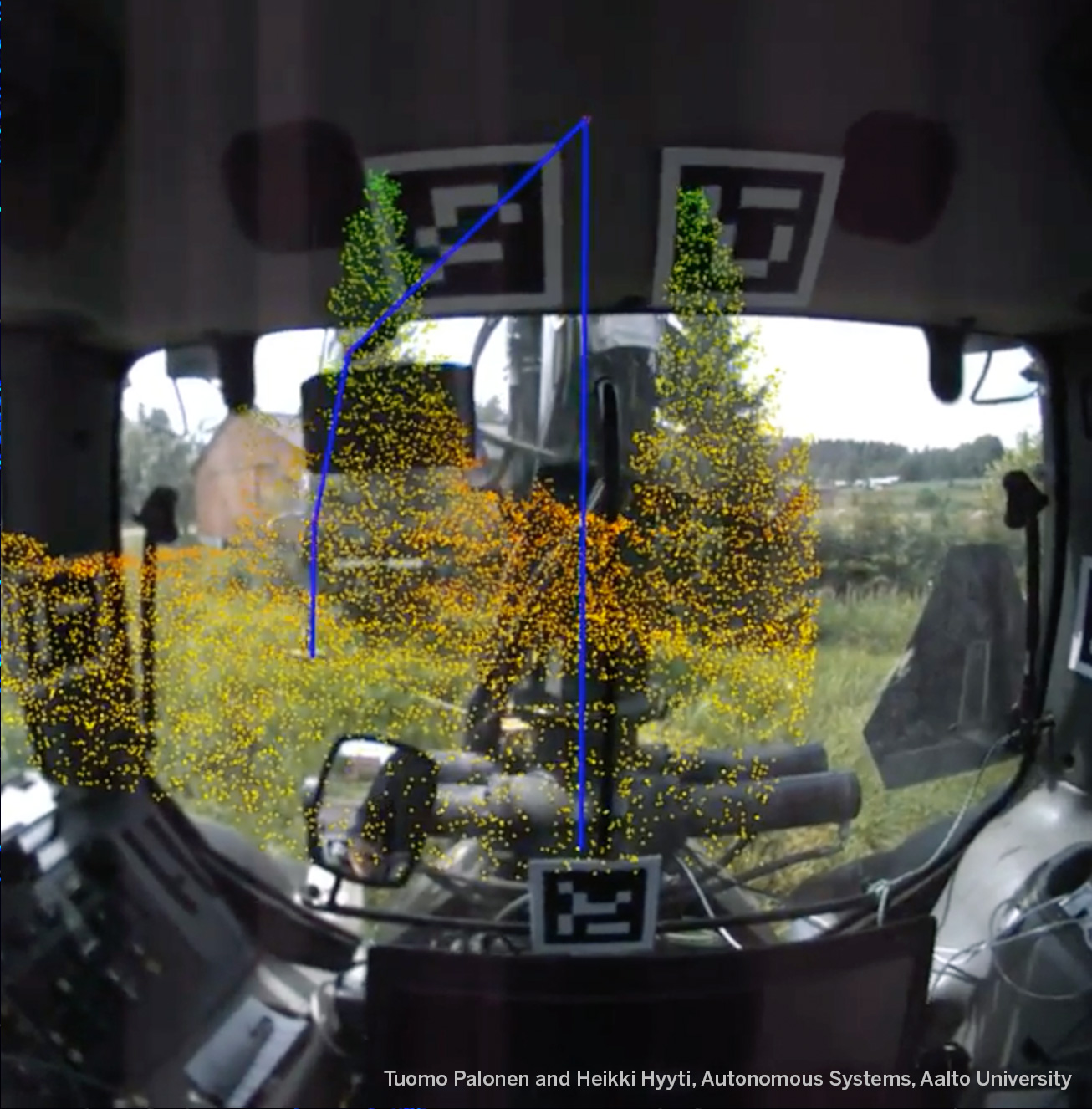

Digitalisation and the improved use of forest asset data are bringing both considerable savings and efficiency improvement to the forest industry. When we know the wood raw material and we can identify the upgrade value of different felling sites as well as the terrain and road features of forests, we can plan the stages of wood supply more efficiently.

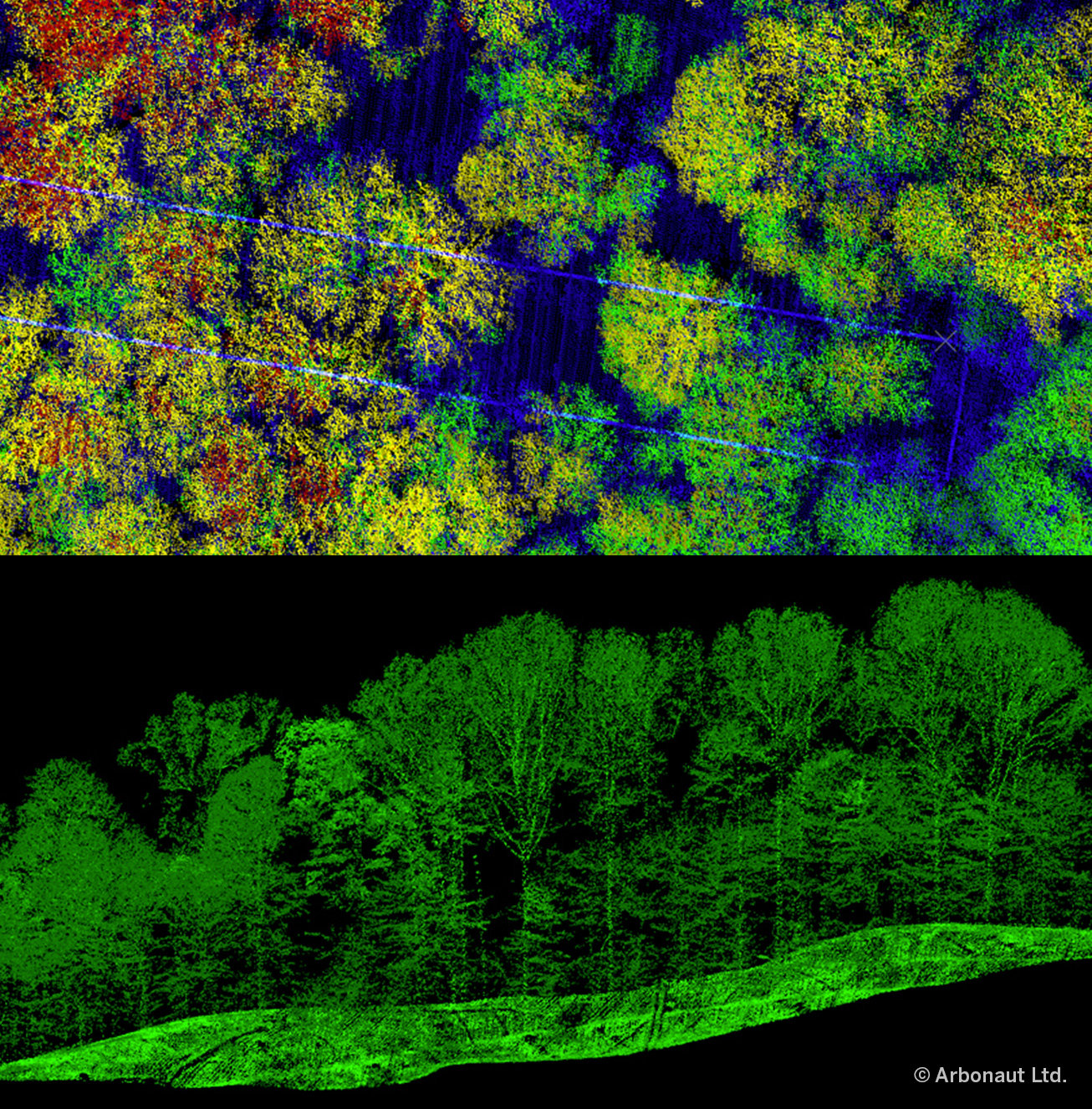

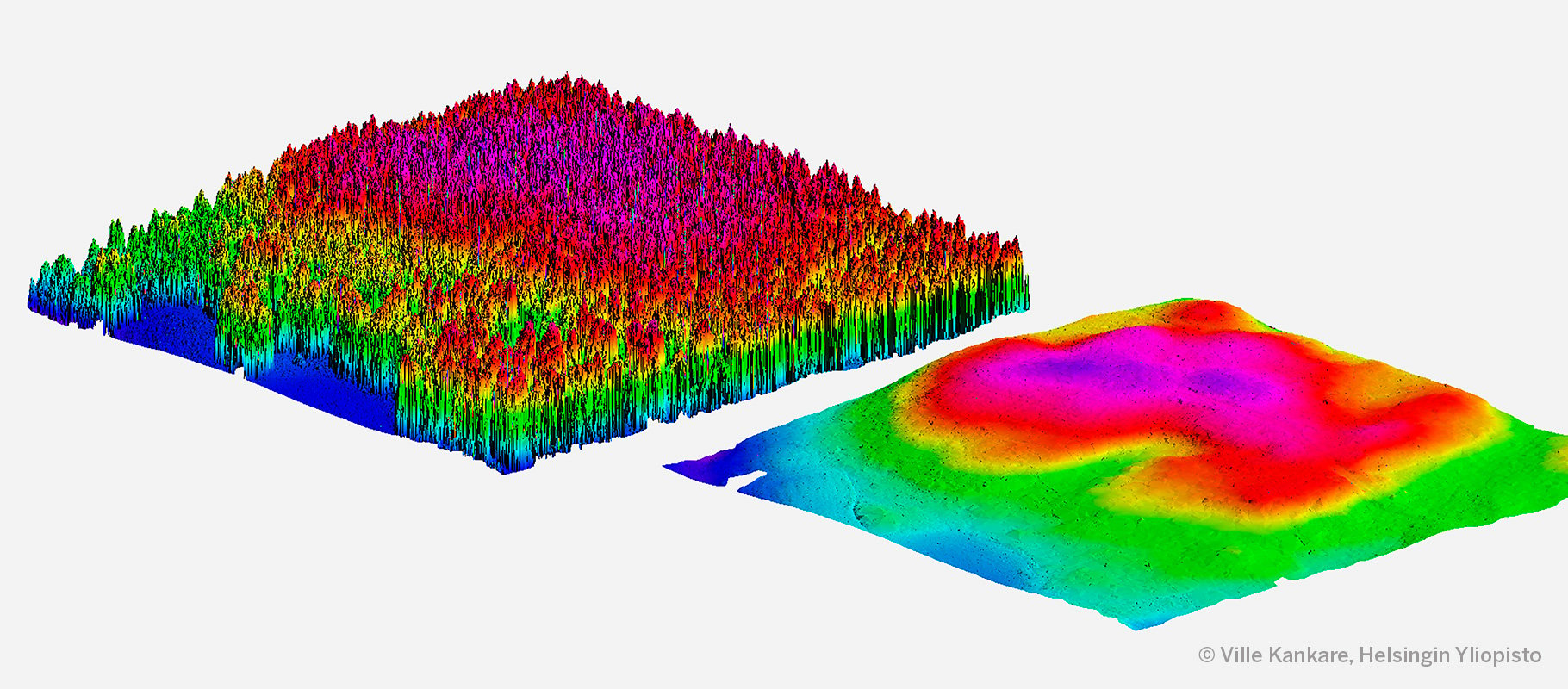

Precision-guided wood supply improves the productivity of the forest industry. When we know what kind of trees there are in each location using e.g. remote sensing, we can plan in advance which raw material it is worthwhile producing from which tree trunk.

“With technology, we can direct wood supply work more precisely, and work phases and visits to the forest can be reduced. It always means savings, both in costs and for the environment,” says Hämäläinen.

It has been estimated that the forest industry could save over EUR 100 million per year in the coming years when it is possible to utilise all the data from forests. These savings make up almost ten per cent of the EUR 1.2 billion annual cost of harvesting and transporting trees. The potential benefits of the digital leap in our forests mean considerable cost savings.

Forest data to support decision-making

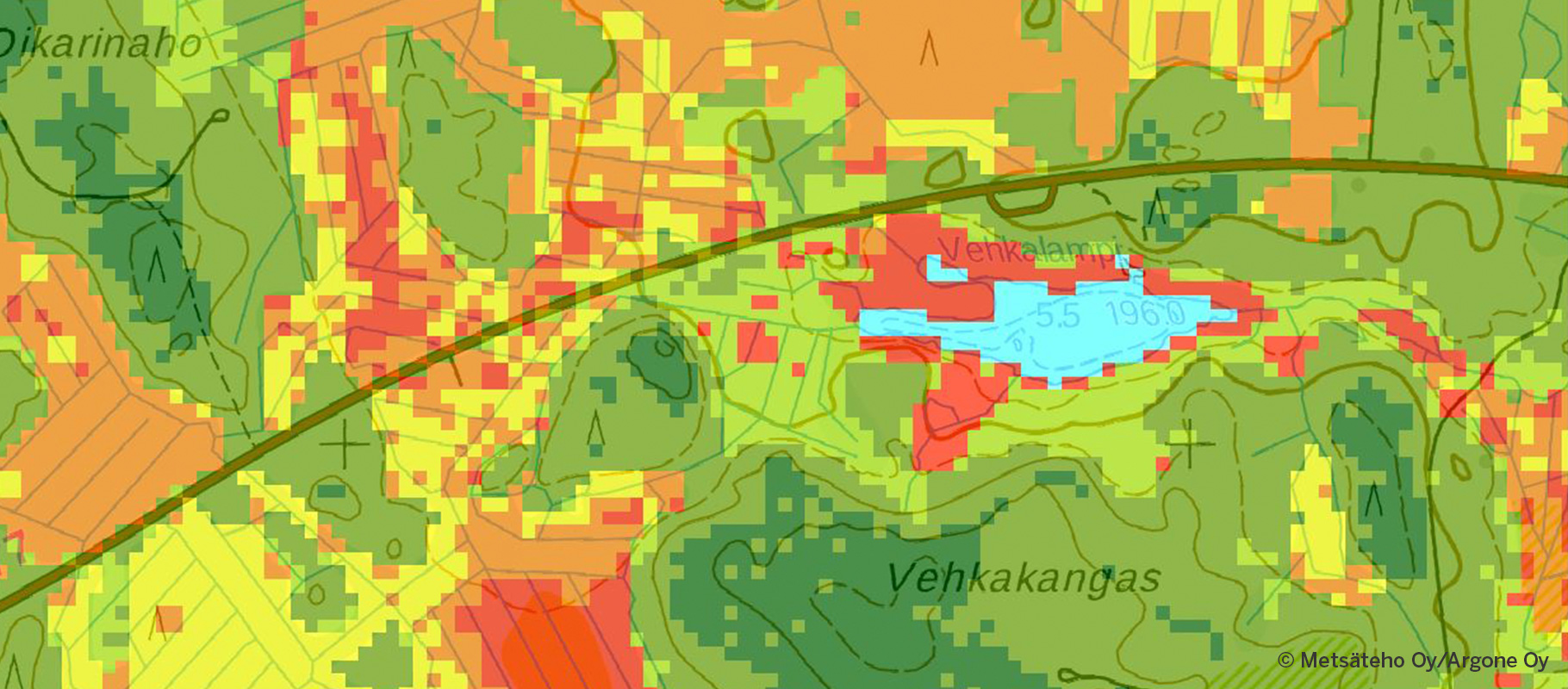

The forest asset data collected by the Finnish Forest Centre contain data on the soil, the amount of trees and their growth, forest management needs and felling possibilities. The data, which can be found in the metsaan.fi service, is now available to all Finnish forest owners, and in future it will also be made available to other forest industry users.

Forest owners will have all the information gathered from their forests. Furthermore, it is possible to give others permission to utilise the information. This way, a forest industry operator could approach a forest owner with a seedling stand management offer.

“Forest asset data is the foundation for all forest operations. It contains valuable information on stands that helps us to understand our forest reserves better. It makes the work of all forest industry operators easier,” says Olli Laitinen, Senior Vice President, Development, Metsä Group.

Thanks to digital forest asset data, a forest owner who lives elsewhere can use the online service to access high-quality information to help in decision-making, irrespective of where they are. “Forest asset data helps forest owners to understand their forest: what kinds of trees, habitat and nature value there are, and how the forest can be used – or left unused – either economically or recreationally. Nowadays, it is possible to calculate what kind of sales income can be made and what costs are incurred from forest management work. In addition, it is increasingly easy to visualise what the forest will look like after thinning or other forest management work,” Laitinen goes on to say.